At 34, Dr. Tomás Bravo had earned a level of respect few veterinarians attained in the glamorous yet secretive world of the Hipódromo de las Américas in Mexico City. He was considered one of the country’s top racehorse specialists. His ethics were impeccable, a rare and valuable quality in a sport where millions of pesos were wagered every weekend.

That cold March morning in 1987, Tomás parked his blue Ford pickup truck in the employee parking lot, a routine he had repeated almost daily for the past eight years. He greeted the security guard, had his usual coffee in the cafeteria, and headed to the stables. “Good morning, Doc,” Marcos Dávila, another of the lead veterinarians and a man Tomás considered a friend, greeted him. “You need to take a look at ‘Fuego Nocturno.’ He’s limping on his left hind leg.”

Tomás nodded, picking up his medical bag. “Fuego Nocturno” was a three-year-old stallion valued at over two million dollars. Any injury could mean the end of his career. While examining the thoroughbred, Tomás was talking with Marcos about the upcoming season. “This horse has potential for the Classic,” he said, carefully palpating the tendon. “But he needs complete rest. No training for two weeks.”

“The owner isn’t going to be happy,” Marcos murmured.

“The owner can call me if he has any problem with my professional assessment.”

That was the essence of Tomás Bravo. He would never compromise an animal’s health for money or pressure. In a sport where fortunes changed hands, and where rumors of doping and fixing were as common as hay, such integrity was an anomaly. Tomás was a good father to two young children and a devoted husband. His life was orderly, predictable, and honest.

That’s why the call he received at two o’clock that afternoon was so disconcerting. It was a number he didn’t recognize.

“Dr. Bravo, I need you to come to the Sandoval Slaughterhouse immediately. We’re on the highway to Toluca. We have an emergency with some horses.”

Tomás frowned. “Sandoval Slaughterhouse? I don’t work with slaughterhouses.”

“Please, Doctor,” the voice insisted. “They’re retired racehorses. Thoroughbreds. Someone abandoned them here, and they’re in very bad shape. I need someone who understands the breed. I’ll pay you double your normal rate.”

Against his better judgment, Tomás agreed. He hated that dark side of the industry: horses that had won prizes and fortunes for their owners, ending their days forgotten or, worse, in an illegal slaughterhouse. If thoroughbreds were suffering, he had to go. He told Marcos Dávila where he was going, and around 3:30 p.m., he left in his blue pickup truck.

He never went home.

When midnight arrived and Tomás didn’t answer his phone, his wife, Sara, began a frantic series of calls. First to the racetrack, then to the hospitals.

“No, Mrs. Bravo,” the night watchman told her. “Dr. Bravo left around 3:30 in the afternoon. Dr. Dávila said he was going to check on something at a slaughterhouse.”

Sara called the police at 2:00 a.m.

Commander Daniel Campos, of the State of Mexico Judicial Police, took on the case personally. Tomás Bravo was well-known in the community, an upstanding man with no history of trouble.

They found Tomás’s truck the next day, abandoned on a dirt road five kilometers from the Sandoval Slaughterhouse. The keys were still in the ignition. His medical bag was on the passenger seat. There were no signs of a struggle. No trace of Tomás.

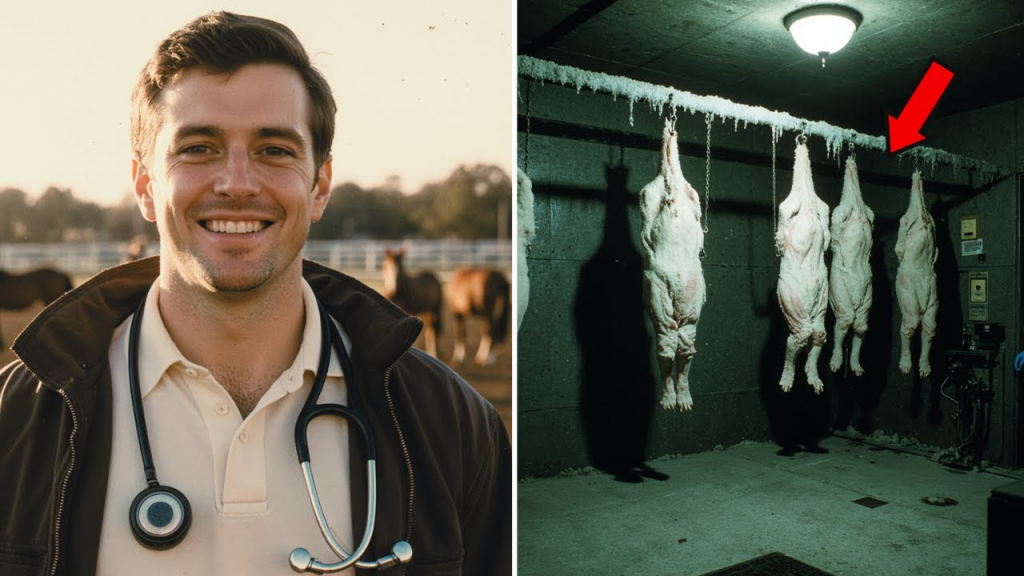

Commander Campos went directly to the Sandoval Slaughterhouse. The place was sinister, a cluster of stained concrete buildings where the smell of blood and death permeated the air. The owner, Roberto Sandoval, was a burly, 55-year-old man with calloused hands and a perpetually sullen expression.

“Veterinarian? I haven’t called any veterinarian,” Sandoval said, spitting on the dirt floor. “We don’t have horses here now. Just cattle.”

“Someone called Dr. Bravo from his slaughterhouse, asking him to come.”

“It wasn’t me. And I don’t have a phone in the office; it broke a week ago. The phone company still hasn’t come to fix it.”

Campos checked. It was true. The slaughterhouse’s phone line had been disconnected for eight days. Whoever had called Tomás hadn’t called from there.

“Can I take a look around?” Campos asked.

Sandoval shrugged. “Go ahead, but you won’t find anything. I don’t know anything about any veterinarian.”

Campos spent two hours inspecting the slaughterhouse. It was a grim place, with hooks hanging from rusty rails in the ceiling and drains in the floor stained with decades of blood. But he found nothing to indicate a crime. Nothing related to Tomás Bravo.

The investigation continued for weeks. They interviewed everyone.

Leave a Reply